Main reference: Story in Sinafinance by Lao Qianzhuang

THERE ARE A few general rules of thumb that investors can follow when trying to determine which listed firms are worthy of attention, and which are lemons headed nowhere.

Let me start off by saying that I have been trying to master this skill for several years, but I still have no foolproof, airtight formula for spotting leaders among lemons.

That being said, there are a few givens in the trade that can at least narrow down the winnowing process and timeframe in sorting the good companies from the bad. Listcos with strong brand recognition and an established product focus are better investment options, says one market watcher. Photo: XtepGood Companies

Listcos with strong brand recognition and an established product focus are better investment options, says one market watcher. Photo: XtepGood Companies

Firstly, good companies that are worthy of your hard-earned investing capital are typically those enjoying upward growth trajectories – both in terms of market share and revenue.

And if they enjoy a market leading or similarly unassailable position for a key product or two in their pipeline, then all the better.

However, while it is important for firms to spread out their risk with a few goods or services in a product portfolio, good companies also have a distinct business direction and focus and rely on a few flagship items or services to drive the bulk of the top line year in and year out.

In addition, high brand recognition and widespread consumer acceptance are traits that good companies often have in common.

For larger firms, especially those that often butt heads with jealous rivals when expanding market share or geographic footholds, it is important that a company’s legal representative is experienced in the field, deeply understands the industry and better yet – himself holds an equity stake in the firm he is hired to serve and protect.

Also, it is of course important to take a good look at a company’s leadership before throwing money its way.

Are the firm’s top executives mainly engaged on a daily basis in improving the product line, enhancing service quality and optimizing management efficiency? Having a solid market position is also a sign of a quality listco worthy of a look. Photo: Chow Sang SangIf so, then it can be considered a good company.

Having a solid market position is also a sign of a quality listco worthy of a look. Photo: Chow Sang SangIf so, then it can be considered a good company.

Furthermore, make sure that the leadership structure is not top heavy.

Companies have trouble reaching consensus and making quick decisions in “market time” when there are several executive directors or vice presidents assigned to essentially perform the same job with inefficient overlaps.

And don’t forget the little guy in the equation.

A good company should also have employees who respect management, are satisfied with their working conditions and compensation, and are therefore most likely to give the firm a 100% effort day in and day out.

Finally, good companies ripe for new investment typically show steady – but not meteoric – share price gains over time.

They ideally should be higher now than they were a year earlier, with a stable upside drive still humming along.

Bad Companies

Firms that can be considered “bad” for investment are those vying for profits in a very crowded, mercilessly-overcompetitive sector.

Worse yet, they aren’t even at or near the top of the heap in terms of profit margins or brand recognition.

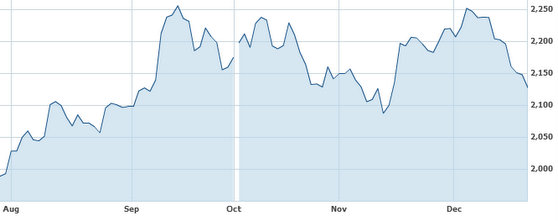

These firms typically rely more on the sudden failure or collapse of their rivals than any in-house innovation or market-changing moves from within their own company. Recent performance of China shares. Source: Yahoo Finance

Recent performance of China shares. Source: Yahoo Finance

Fickleness is not becoming to a good company, and bad ones will change business direction or product focus with the weather, which looks to investors like a rudderless management grasping at straws.

Also, shifting revenue drivers from one product or service to another, or a bottom line swinging back and forth from red to black and back to red again are signs of indecision and directionless management and a lack of cohesive business strategy.

In addition, bad companies often see their share prices stuck in an “elevator” – that is, closing prices rising and falling drastically on a frequent basis.

Finally, when the bulk of the investing community can’t tell you what a particular company does (without searching on their tablet first), then it’s probably not a good enough company to deserve your money.

Of course there are exceptions to these rules of thumb, including the lack of brand recognition for an upstart SME that may be highly technical in nature and serve an upstream niche clientele.

For these firms, brand recognition is not critical to success.

But generally speaking, “good” and “bad” companies generally share the characteristics as outlined above.

See also:

CHINA SHARES: Why 2014 Is Looking Better