Andrew van Buren

IT WAS ONLY a few short years ago that China, for the first time in its modern industrial history, seemingly overnight made the grand transition to net exporter of steel from net importer.

And in recent years, overseas iron ore miners and oceanborne shippers have hit paydirt, riding on the back of China’s phenomenal ascent to become the world’s biggest steelmaker and iron ore importer (thanks in large part to the low Fe content of domestically-mined equivalents).

In fact, seaborne cargo rates from Brazil, India and South Africa to China (and to a lesser extent from Australia given the relative proximity) were in fact the chief culprit behind the shocking annual price increases China paid since roughly 2003.

However, as far as cargo shippers are concerned, the recent financial crisis has severely rocked the boat.

The ongoing global economic malaise, coupled with Chinese steelmakers’ newfound hyperdependence on external demand, has hit commodity firms and the shipping companies that move their products across oceans especially hard.

Mercator Lines shares have soared 103% since the start of May 09, closing at 33.5 cents yesterday.

Several erstwhile iron ore mining behemoths like Australia’s BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto, as well as Brazil’s CVRD, have become low hanging fruits for cash-rich Chinese SOEs to pluck at will.

But while non-Chinese shipping firms are not seeing the white-hot M&A interest from Chinese firms that is visited upon the miners, they are still facing a dire situation due to the rapid slackening in China’s demand for higher quality imported iron ore.

In fact, Credit Suisse said in a report on Thursday that global dry-bulk shipping lines need an “unprecedented” surge in Chinese iron-ore imports to fully use their expanding fleets.

The Swiss banking group said Chinese imports of iron ore – the chief raw material used in the production of finished steel – are expected to decrease over the next several months.

Credit Suisse said the global dry-bulk fleet should rise 6.9% this year, as shipyards deliver vessels ordered during a trade boom that ended last year.

The new ships will enter service as Chinese iron-ore imports, a key market for bulk lines, head for declines because steelmakers are working through inventories, the report said.

Experts elsewhere agree that the near-term future is bleak. “Imports of iron ore will fall in the near future. We will see a widening gap between demand and new ship deliveries in the second half,” Bloomberg cited Jack Xu, an analyst at Sinopac Securities Asia Ltd in Shanghai, as saying this week.

The Credit Suisse report went on to say that in order to utilize the expanded fleet, full-year Chinese iron-ore imports would need to rise 63% from 2008.

That would mean an average rate of 67 million tons a month for the rest of the year. Instead, the monthly shipments could average as much as 52 million tons, under the Swiss bank’s most optimistic forecast, or as little as 42 million.

The bulk fleet is set to surge as shipyards are working through orders with a combined capacity of 68% of the existing fleet, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Overall global dry-bulk shipping demand will likely fall 3.4% this year, Credit Suisse concluded.

UOB Kay Hian is also hardly sanguine on any sudden turnaround in Chinese steel mills’ demand for imported iron ore, and the blessings that brings to global cargo shippers.

This week, it reaffirmed its “underweight” recommendation on regional dry bulk shipping. It said the Baltic Dry Index (BDI) will likely reverse on China's lower iron ore imports and easing port congestion, thus hitting shippers’ margins.

UOBKH said China's iron ore imports have been rising sharply in the last 3 months (Apr 09: +33% year-on-year to 57mt) despite its sluggish crude steel production growth (Apr 09: -2.8% to 43mt).

“This was mainly because traders were stockpiling iron ore in anticipation that prices would rise (according to the China Iron and Steel Association). This has led to a near record high iron inventory of 70mt, resulting in many ore carriers congested at Chinese ports,” the note said.

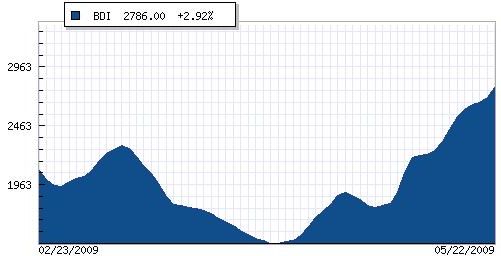

Baltic Dry Index stood at 1463 on Apr 8 but closed at 2786 on May 22, up 90%

BDI has risen 250% year-to-date from an extremely depressed level due to, UOB Kay Hian said, 3 reasons:

a) some easing in trade financing,

b) high iron ore cargo shipments in the past 3 months, and

c) the port congestion in turn soaks up more vessel capacity, boosting spot freight rates.

“We expect China's iron ore imports to ease, which in turn will ease port congestion. This will have a double-whammy impact on spot freight rates. The BDI breakeven level for most dry bulk shipping companies is about 2500. At the current BDI level of 2,707, the profit level remains low for most companies. They will likely make losses in spot trades when the BDI reverses.”

China's Ministry of Industry and Information Technology has issued a circular to authorities to control the number of steel traders and to crackdown on stockpiling.

“We believe the current rally in BDI is not sustainable and will likely come off. We recommend selling dry bulk shipping stocks into strength. They have had a good run in the current stock market and BDI rallies. We remain UNDERWEIGHT on the dry bulk shipping sector in view of a large influx of newbuilds into the market from 2H09 onwards.” UOB Kay Hian added.

UOB KH analysts Nancy Wei and Esther Sim

In another report, Paul Slater, chairman and chief executive of First International, said that more than half of the shipping companies with stock exchange listings could slide into bankruptcy or administration proceedings in the next year as their cash drains away, citing a senior industry figure.

Slater forecast that the next 12 months would be “really painful” for the three main shipping sectors of containerships, dry bulk and tankers.

However, Slater’s views on the fate of the public companies was described as “alarmist” by a leading representative of the financial and shipping industry in New York, where most of the stock market listings of the past decade have taken place.

Slater pointed out that there were now more than 30 public shipping companies on US stock exchanges, about 60% of which were not public at the beginning of this decade.

“The average reduction in market value of the US public companies is somewhere between 60-68% in 12 months,” he said. “That is huge in any industrial sector.”

Even more important was the lack of cash-flow, Slater said.

“We’re in a situation where revenue streams are barely covering operating costs,” he said.

Recent shipping stories:

YANGZIJIANG: Why no cancellation of dry bulk orders?

ASL MARINE: Order book is a whopping S$663 million!

RICKMERS MARITIME: 2.25 US cents dividend for Q4