Photo by Sim Kih

AS THE AUTO GATE of the house in Bukit Timah swung open and I drove through, it struck me that I was meeting a very rich Singaporean who, strangely enough, is one of the least known.

His driver stepped up and, as I eyed the swimming pool longingly, showed me to a small single-storey building next to the main double-storey home.

I quickly took in the grounds – some 23,000 sq ft, the equivalent of 12 terrace houses – and was struck by its lush greenery and seclusion. Opulence didn’t come to mind, though.

As I stepped into the room, Mr David Lam – ranked among Singapore’s 40 richest people by Forbes magazine last year - took aim at a ball on the billiard table, and greeted me.

We settled down on a sofa next to a large guest bedroom and, as we began to chat, it became apparent that he was ambivalent about publicity. “I’m a simple man. It’s better to be successful quietly.”

He doesn’t believe in talking about money publicly, a trait that stems from when he nearly lost everything in a trading business when he was in his early 30s. “I learnt that you wouldn’t know where you’d be tomorrow. So don’t act ya-ya or talk big when you have some money.”

Mr Lam, 56, had stayed out of the limelight also because his business didn’t need it. As he explained, his business didn’t engage consumers locally. All his clients are businesses and they are based outside of Singapore.

I told him that the story of his business success would inspire future entrepreneurs. Indeed, it’s an amazing story: From day one, he dealt only with global corporations. His first client was Goodyear Tire, no less.

The business began with Mr Lam’s Eureka experience, as it were, when he witnessed wooden crates containing raw rubber falling from a lorry in Thailand. Wood splinters from the crates pierced the rubber bales, and workers had a difficult time removing the splinters.

Mr Lam recalled: “I thought I would have a big market if I could come up with non-wood packaging. And if the packaging could be re-used frequently, it would be economical and environmentally-friendly.”

He designed and re-designed containers – which would be called Intermediate Bulk Containers – and sent them to potential clients in the US and Europe for trials that lasted for two years.

Made for stacking on top of one another when filled with cargo, Goodpack’s high-tensile steel containers are nestable when empty, so there are large savings in transportation cost.

Best of all, they can be used again and again, unlike conventional wood crates which are thrown away after being used once, adding to landfill and environmental problems. Goodpack’s containers are lightweight for ease of handling and yet robust in order to endure ship journeys.

Recognising the global potential of his invention, Mr Lam filed for a patent in London and was successful. He went on to obtain patents in key markets such as Europe, the United States and Japan.

In 1991, when Goodpack started shipping natural rubber from various countries of production to Goodyear, it changed the way rubber had been transported for more than 100 years. “I don’t think I invented anything great, but it was something that the world needs,” said Mr Lam, chairman and managing director of Goodpack.

Listed on the Singapore Exchange in 2000, Goodpack has emerged as the No.1 in the world in its business of supplying and leasing containers to ship natural rubber, synthetic rubber, fruit juices and other products.

Today, it owns 1.7 million containers while its nearest competitor has 60,000 containers of a different design. Goodpack’s containers are ever on the move in 68 countries around the world, shipping cargo, being emptied and cleaned, or being transferred to another destination for loading again.

Goodpack transports about 45% of the 6.3 million tonnes of natural rubber produced globally every year. The rest is moved by wood crates from developing countries such as China, India and Russia – but that will change in future as Goodpack is working hard to increase its customer base there.

“That’s something I am very proud of, especially when you consider that Singapore doesn’t produce rubber at all. One day, hopefully, we can become No. 1 for synthetic rubber. About 14 million tonnes are produced every year, much more than for natural rubber.”

Non-stop growth

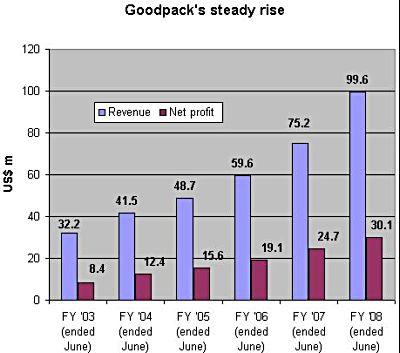

Goodpack’s sales and profits have grown non-stop since 1995, the earliest year that the company's financials were published in its prospectus for its initial public offer in 2000.

Just take a look at this snapshot of its past five years:

* FY ’03 (ended June 2003): Sales achieved was US$32.2 million while net profit was US$8.4 million.

* FY ’07 (ended June 2007): Sales have more than doubled since FY' 03 to US$75.2 million and net profit more than tripled to US$24.7 million.

All that profitability has made Mr Lam rich. His 34 per cent stake in Goodpack is worth about $267 million even in the current stock market slump. Given the growing demand for his containers, he is driving Goodpack to capture an even greater share of the market.

How has he invested some of his wealth, I wondered. He let on that he has two investment properties and shares in other companies – in addition to his home which he bought for $6 million about 10 years ago. He stopped short of giving away more financial figures.

He is passionate about cars and owns a Jaguar XJR, the latest in a long line of Jaguars that he has owned since he could afford them. “If you ask me to go to a car show, I’d love it. But I won’t spend too much on cars.”

He won’t buy expensive shirts either, so $500 ones are out. And when it comes to mobile phones, “so long as they can ring, that’s good enough for me.” He tends to get his phones for free as he waits until it is time to renew a subscription contract for the phone line.

He said in mock horror that his friends wear watches costing six figures and even own a collection, but he is happy with his $4,000 watch. It is one of only two watches he owns, the other costing $2,000.

He is not particular about food: “I’m easy. When I take my family out, I will let my children decide what we will eat for that day. If they like Japanese food, I will eat Japanese.”

His own favourite fine dining restaurants are Tung Lok Signatures in Vivo City, Hua Ting Restaurant in Orchard Hotel and Peach Gardens in OCBC Centre, where he would take business clients.

“If you ask me ‘On your own, what would you eat?’ I’d say porridge in a coffee shop in Simon Road, off Upper Serangoon Road. Businessmen of my generation just love it but not our children.”

If he has one weakness, it is shoes – brands such as Testoni and Armani.

“I love good and comfortable shoes, maybe because they enable me to walk with confidence. And maybe because when I was young, my family was sometimes too poor to buy me a pair of school shoes.”

For him, real happiness is a golfing holiday with his three sons and wife of 26 years, Ivy, in the cool climate of Kunming in southern China.

“I enjoy a golfing holiday with them a lot - but it’s getting more difficult to get them together,” said Mr Lam. His eldest son, Zhi Long, 24 is studying in a local private university while second son Zhi Qun, 18, a national golfer, is serving national service. A third son, Zhi Xiu, 17, is studying in the United States.

Mr Lam offered a nugget of parental advice: “If you have children, you must spend a lot of time with them before they grow up. I didn’t do enough of that as I was busy traveling and building up Goodpack.

“I will make up for that. My dream is to buy a plot of land, build four homes on it, so we all would be living near to one another. Every Saturday night, we can come together and eat as one big family.”

Recent story: GOODPACK: First major foray into China

This article was first published in a recent edition of Pulses magazine, and is reprinted here with permission